5.5 miles

franklin hill turn around

26 degrees / feels like 20

light snow / wind: 15 mph gusts

100% snow-covered

Winter! Woke up to another dusting — maybe an inch? — on the ground. Wore my old yak trax, the ones I got 3 or 4 years ago that are worn down, but still work. Mostly I’m glad I did, but several times snow clumped up in the grooves. Was it because of the yak trax, the high water content of the snow, or something else?

My Favorite Things

- the feel of snow under my feet — more interesting than boring asphalt

- the creaks and crunches of that snow

- greeting Mr. Morning! and Dave, the Daily Walker

- 3 geese flying west — I heard their harsh honks first, echoing across the gorge, then they appeared, flying low near the trestle

- open water, brownish-gray

- in the second half of the run, the snow stopped and the sun was trying to pierce through the thick clouds. Everything looked slightly blue — the snow, the sky, the trees

- the graceful runner who passed me, their feet bouncing up and down, up and down

- in the first half, when it was much darker, the headlights cutting through the dim

- running up the Franklin hill — I felt strong and free, untethered

- ending at the ancient boulderS after (almost) sprinting up the hill — my winter running tradition

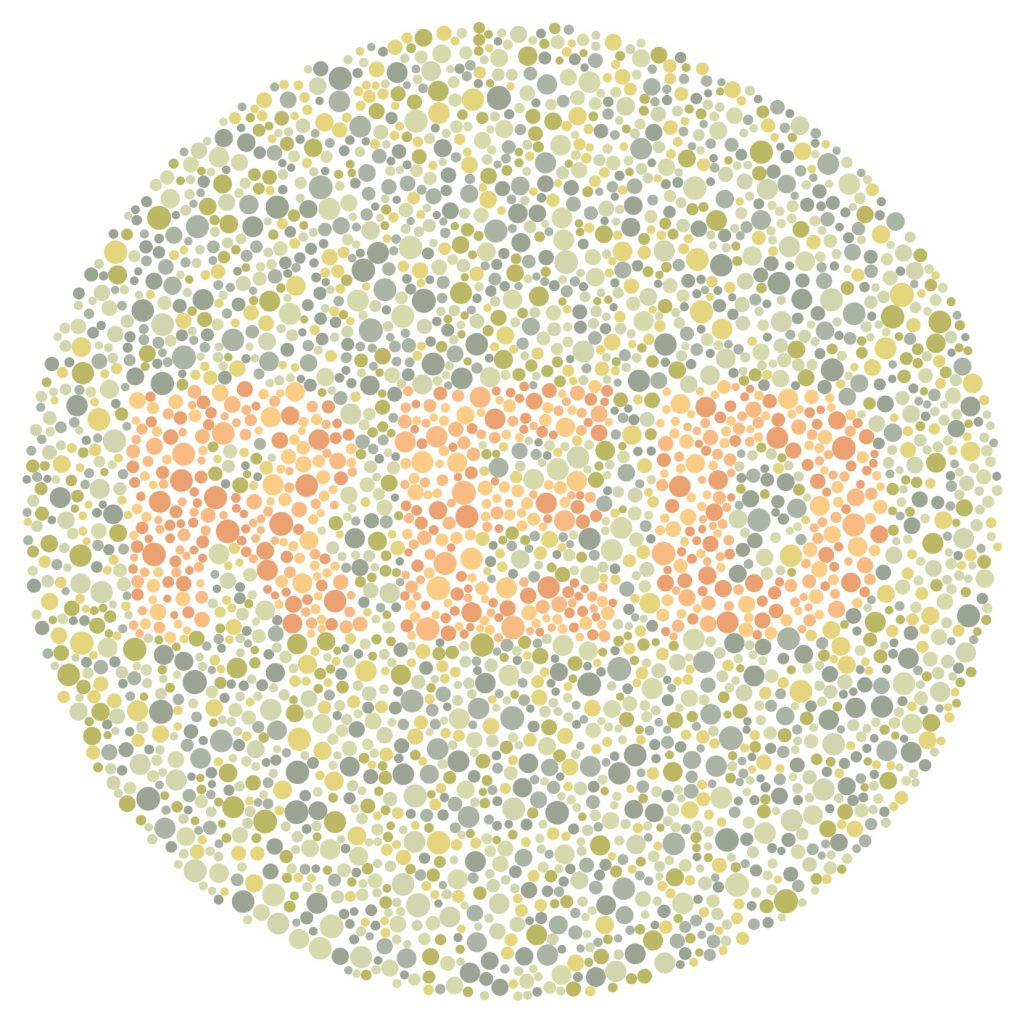

Ishihara colorblind plates as form

Still thinking about my next series of vision poems. A plan seems to be forming. Here’s what I wrote:

A series of colorblind (Ishihara) plates describing how I see and don’t see color and what that means for how I move through the world.

The actual series of plates for the test are 38. I think that might be too many. Each poem will consist of 2 plates: the “actual” plate (designed by Scott) with the circles and the hidden message. In the original, it’s numbers. In mine, it’s a word that can stand alone as a poem, but also (might) connect with the other plate words and is the unifying theme for a prose poem that is on the second plate. This second-plate poem will (most likely, but maybe not?) take the form of the circle of the plate. Tentatively, I’m imagining it as a prose poem, but it might be its own thing, a series of words, descriptions related to seeing and not seeing color.

The plates will be divided into different topics related to color:

a story about why this test matters to me

what everything looks like, how it feels

struggles/quirks/strange

a focus on gray — contrast — light and dark, not in color

Scott found something on github that enables you to easily (or easily for Scott) design your own plates. Here’s a sample of what he did. He put the word red in it. I’ll take his word for it because I can’t see the letters at all.

today’s gray theme: duck duck gray duck

Still thinking about gray this month. Today, inspired by the wonderful geese I heard while running, I’m thinking of the passionate way Minnesotans defend their name for the childhood game, Duck Duck Gray Duck over what the rest of the country calls it, Duck Duck Goose. I am not one of those passionate Minnesotans because I grew up on the east coast in North Carolina and Virginia. We played Duck Duck Goose. I’m fine with calling it Duck Duck Gray Duck, but I don’t really care. Scott does. No matter how often we’ve discussed it, he gets fired up every time the topic is mentioned. It is fascinating to me that Minnesota is the only state that uses gray duck and not goose, especially thinking about how many kids who grew up in Minnesota probably have a moment when they realize that not everyone else calls it that.

Because I’m that person, I had to wonder, are gray ducks rare? Yes, especially in Sweden. According to my quick googling, the most common color for ducks in Sweden is blue.

I already have 2 wonderful poems about wild geese — Wild Geese/Mary Oliver and Something Told the Wild Geese/Rachel Field — but I can always use another!

The Geese/ Jane Mead

slicing this frozen sky know

where they are going—

and want to get there.

Their call, both strange

and familiar, calls

to the strange and familiar

heart, and the landscape

becomes the landscape

of being, which becomes

the bright silos and snowy

fields over which the nuanced

and muscular geese

are calling—while time

and the heart take measure.