3.5 miles

river road trail, south/under ford bridge turn-around/river road trail, north/Winchell Trail, north

48 degrees

Yes! I ran on the trail all the way today: headed south on the upper trail, turned around just past the ford bridge, then back home on the lower trail. Heading down to the lower (Winchell) trail, I admired the sparkling river again. I wish the lower trail was longer; I really enjoy being a little closer to the river and running under the trees and on the edge of the bluff. It was mostly sunny, but occasionally the sun would hide behind a cloud and the trail and the trees would turn from lime greens and dark browns to dull gray.

Ran past the 42nd street sewer pipe and I listened to the water, I figured out some words that fit between dripping and gushing (which was my problem from yesterday’s run): falling, flowing, (a gentle) flushing. As I tried to hold onto those words so I could remember them for this entry, I heard a sharp beeping or tweeting noise. At first I thought it was a bird, then I realized it was a truck backing up. Then I thought: when we hear the beeping of the truck, do we need to put the idea that it’s a truck backing up into words, or do we have a more immediate understanding of it? How intelligible/recognizable in language do these sounds need to be for us to know and respond to them? Thinking I might forget this thought, I decided to stop at the top of the short but steep hill near Folwell and record some notes.

I was inspired to think about sound and syllables and language because of my bird poem for the day. I became aware of it after two different bird articles (or books?) that I read yesterday used a bit of it for an epitaph. I think they both used this bit:

is it o-ka-lee

or con-ka-ree, is it really jug jug,

is it cuckoo for that matter?–

much less whether a bird’s call

means anything in

particular, or at all.

Syrinx/ Amy Clampitt – 1920-1993

Like the foghorn that’s all lung,

the wind chime that’s all percussion,

like the wind itself, that’s merely air

in a terrible fret, without so much

as a finger to articulate

what ails it, the aeolian

syrinx, that reed

in the throat of a bird,

when it comes to the shaping of

what we call consonants, is

too imprecise for consensus

about what it even seems to

be saying: is it o-ka-lee

or con-ka-ree, is it really jug jug,

is it cuckoo for that matter?–

much less whether a bird’s call

means anything in

particular, or at all.

Syntax comes last, there can be

no doubt of it: came last,

can be thought of (is

thought of by some) as a

higher form of expression:

is, in extremity, first to

be jettisoned: as the diva

onstage, all soaring

pectoral breathwork,

takes off, pure vowel

breaking free of the dry,

the merely fricative

husk of the particular, rises

past saying anything, any

more than the wind in

the trees, waves breaking,

or Homer’s gibbering

Thespesiae iache:

those last-chance vestiges

above the threshold, the all-

but dispossessed of breath.

aeolian (def):

(adj) giving forth or marked by a moaning or sighing sound or musical tone produced by or as if by the wind.

(adj) borne, deposited, produced, or eroded by the wind

god of the winds (greek)

aeolian mode: natural minor scale

iache (noun): any kind of inarticulate cry; most likely it is an onomatopoeia, an imitation of human sounds that are not language; most frequently used of the shouts that accompanied Greek religious ritual

thespesiae (adj): divine, especially in the sense of mysterious or inaccessible to human understanding

terms from Homer’s Odyssey, found in this helpful study guide for the poem

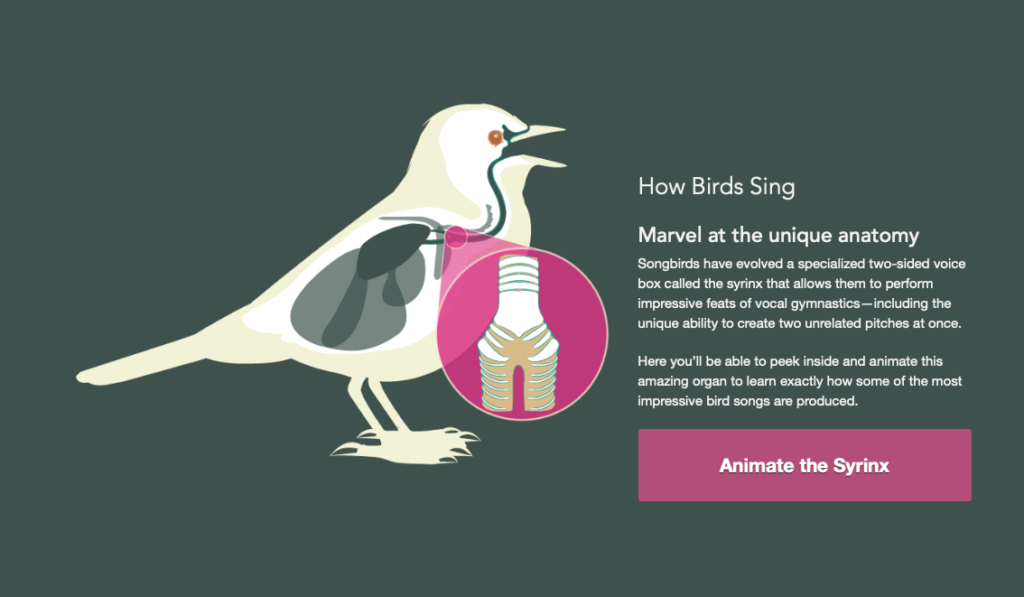

Click on this image to see how the syrinx works over at one of my favorite bird sites: All About Birds

Her line about the “pure vowel/breaking free” made me think of Robert Bly and his discussion of vowels in the documentary‘ STA and I watched the other day. He read this bit from his long poem, “As If Someone Else is With Me” from Morning Poems:

So it’s a bird-like thing then, this hiding

And warming of sounds. They are the little low

Heavens in the nest; now my chest feathers

Widen, now I’m an old hen, now I am satisfied.

And here’s some helpful advice for starting to think about birding by ear:

How to “Bird by Ear”: Getting Started

To speed up the learning process, don’t just listen passively: Focus and analyze what you’re hearing. Describe the sound to yourself, draw a diagram, or write it down. If it’s a complicated song, figure out how many notes it has. Do all the notes have the same tone and vibe? Does the tune rise or fall? Can you adapt the “syllables” into words and make a mnemonic? The Barred Owl, for instance, hoots Who cooks for you, and the Common Yellowthroat sings Wichity-wichity-wichity. But you don’t have to just settle for published mnemonics; listen carefully and then invent your own. Little memory hooks like these will make birding easier the next time around. And as always, repetition helps.

Birding by Ear, Part One/ Audubon Society