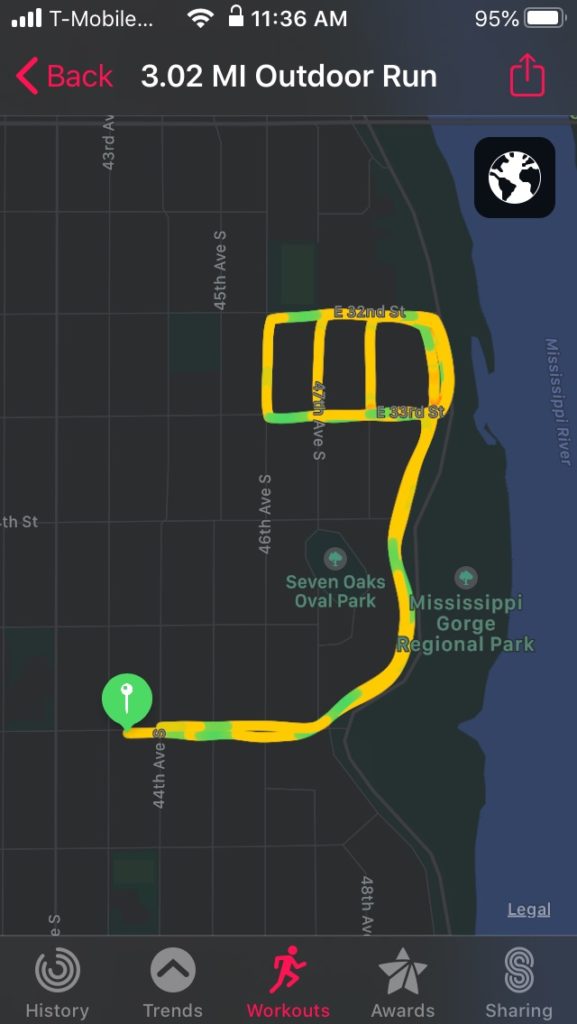

3.25 miles

hill “sprints”*

67 degrees

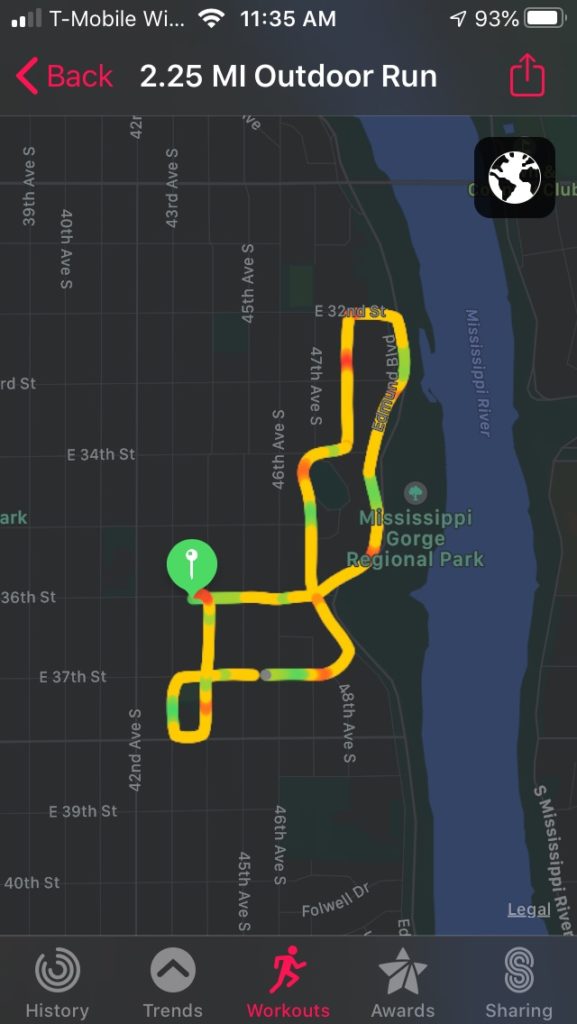

* Warmed up by running north on 43rd ave, east on 32nd, south on Edmund. Jogged down the hill beside the Welcoming Oaks, then much faster, sometimes sprinting, up the hill 4 times.

Decided to try hill sprints for the first time today. I’ll call it a success because I set out to do 4, and I did 4. But it was difficult and I only ran hard all the way to the turn around on 2 out of the 4. I’m sure I’ll get better if I keep doing these. Listened to a playlist as I ran. Didn’t think about anything but getting to the top of the hill and then trying to slow my heart rate as I ran back down.

I ran through the neighborhood as a warm-up. So many beautiful leaves! Several bright red trees. One or two orange ones. A cluster of yellow. I could smell the dry mustiness of decay. Saw lots of acorns on the ground. Too many squirrels looked like they might dart out in front of me.

mood: curiosity

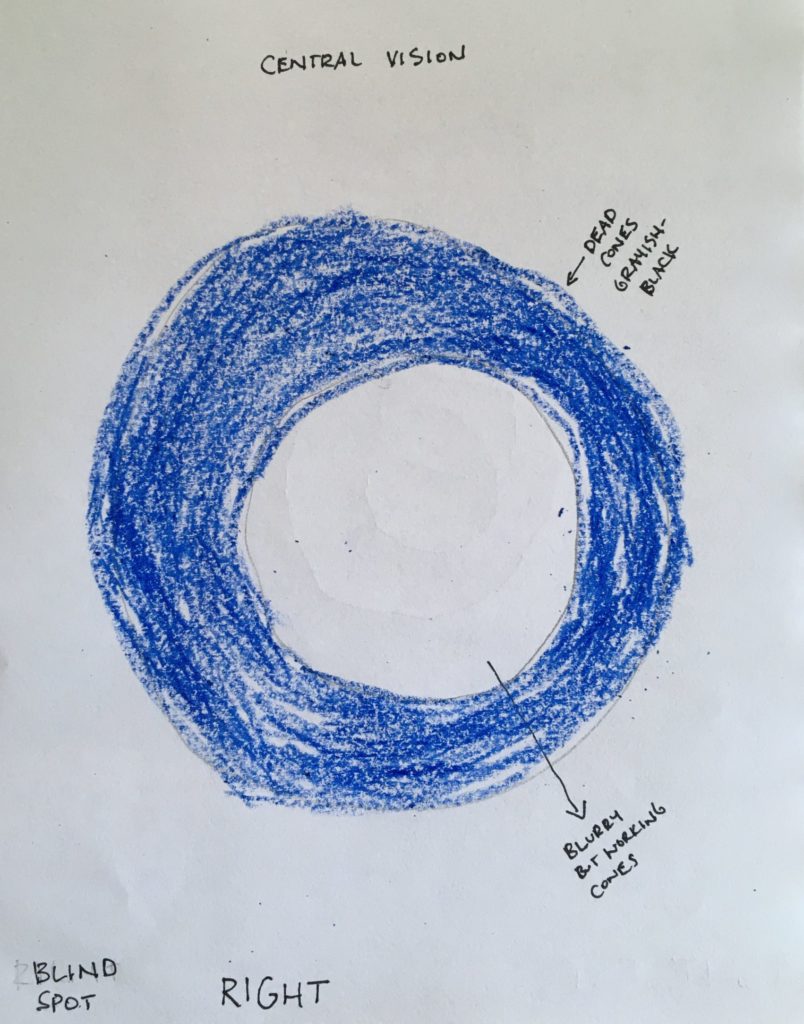

(I wrote this bit when I woke up this morning. It’s a very rough draft, but gives me some things to work with,\.) Before I was diagnosed with cone dystrophy, I never thought much about my vision. I never imagined that I would lose it. Even though I had been having problems for years seeing things—seeing the cursor on a computer or a ball being thrown at me or a bird in the sky—I never connected those problems with bad vision. I thought it was something else, maybe a weird quirk in my brain? Is this the wonder of the brain, its ability to work with limited resources, concealing how damaged our vision is?

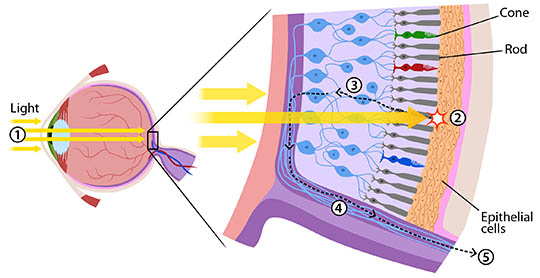

I was never curious about my vision or how it worked. The only thing I remember from learning about how we see was the image of the inverted tree, entering the eye upright, then shrinking and flipping around at the back of the eye. I knew the terms retina (I think), pupil, iris, but I didn’t know the retina was a thin layer of cells lining the back of your eye or that at its center was the macula and in a pit at its center was the fovea where some of the most important photoreceptor cells reside, waiting to convert light into nerve signals that travel through the optic nerve to the visual cortex. I don’t ever remember hearing about rods or cones until my eye doctor explained that my cones were scrambling. I didn’t think about blind spots or try to find mine or wonder too often about how much of what I saw was real or illusion. If I ever thought about the limits of my perception, it was in the abstract, after studying the empiricists in my Modern Philosophy course in college. And a blind spot was something you had in relation to your biased and limited world view.

I suppose I should have been curious about these things, I should have wanted a basic understanding of vision, but it wasn’t until my brain was unable to hide the effects of my diminishing cones and I learned I was losing my central vision that I payed attention. Part of this is because I take my body for granted when it’s working. Why question or scrutinize it when its doing its job? Part of this is because I don’t want to know how it works because once I know, I might think too much about how easily it might not work. And part of this is because I struggle to remember or understand anything with scientific jargon.

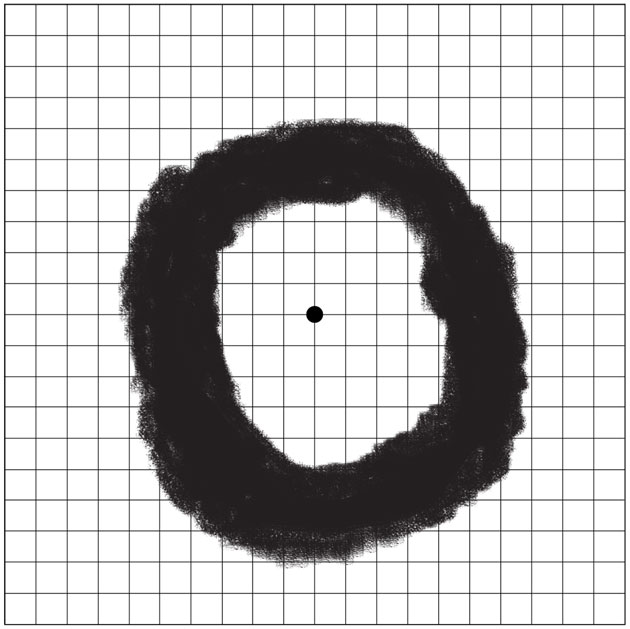

But now, I’m curious. And I’m finding joy in learning about ganglion cells and the optic chiasm and the fovea and how many cone cells are in it and why they’re called cone cells and how the brain handles a lack of visual data (recalling past images, making stuff up) and how optical illusions work and the different types of scotomas and how to use eccentric vision (EV) to compensate for a loss of central vision and when the blind spot was first written about (1668) and two different Charles’s: King Charles II who loved to execute people with his blind spot and Charles Bonnet who first described the trippy visual hallucinations some people experience as they’re losing their vision.